“How can we use mobile technology to improve education in developing countries?”

“What are the roles of NGOs, the private sector and research institutions in contributing to mobile education?”

“Which mobile technologies are most versatile and appropriate for interactive teaching in poorly resourced classrooms?”

These were some of the questions posed by moderator Dr Niall Winters, of the London Knowledge Lab, at “Mobile technologies for education: The experience in the developing world.” Held on 30th March, this panel discussion was the latest event in the Humanitarian Centre’s year-long focus on ICT4D. It was sponsored by Cambridge Education Services and co-hosted by the Centre for Commonwealth Education (CCE) at Cambridge University’s Faculty of Education. CCE’s ethos of ‘offering constructive challenges in a spirit of collaborative inquiry’ imbued the panel presentations and the discussion which followed; mobile education (m-education) was put ‘to the test’ as a viable option for resource-poor classrooms in Africa.

All panelists highlighted the idea that m-education is less about the “m”—that is the mobile technology itself—than it is about the educational innovations which the technology facilitates. The evening almost passed without the perfunctory showdown between Android tablets and second-hand Nokias. But even when this debate arose, the conversation focused on the needs and context of the teachers and learners who use the technology, rather than the gadgets themselves. Niall Winters described the challenge of finding a truly appropriate technology for a resource-poor school (i.e. durable, inexpensive) that is also advanced enough to address complex educational needs. He suggested that any discussion on m-learning must take into consideration “embodied practice”: understanding the everyday activities and behaviours of the learners.

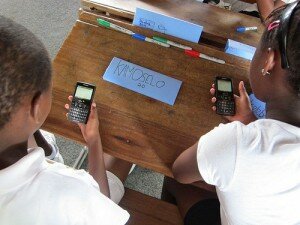

Dr Bjoern Hassler and Dr Sara Hennessy, from the CCE, demonstrated the way in which a pilot project, OER4Schools, can transform the “embodied practices” of teachers and learners, at least temporarily. OER4Schools introduced new technologies to support interactive learning in Zambia. As it changed the learning tools, it also transformed pedagogy of the classroom. Dr Hennessey spoke about enthusiastic teachers, keen to move away from a “chalk and talk” approach, towards interactive and dynamic student activities. Images of students working together on problem solving activities over shared tablets illustrated her points. Although the first stage of this project has finished, they have left a lasting legacy in a classroom that heard “conversation” rather than “noise” for the first time.

Another pilot run by local charity Cambridge to Africa, presented by founder Dr Sacha DeVelle, pairs hearing and deaf children (girls) in a training programme on mobile phone usage for classroom participation. This social inclusion project created unprecedented interaction between hearing and deaf children and teachers, as well as social capital for deaf girls, bolstering their self-esteem. Dr DeVelle pointed out that the third millennium development goal, gender equality, will not be reached if women and girls with disabilities still face exclusionary practices. By extension, we might infer that there will be no ICT4D revolution without social inclusion.

Geoff Stead, of TRIBAL, picked up the thread of inclusivity by focusing on a partner project called M-ubuntu. Ubuntu is a Bantu concept that posits, “I am what I am because of who we all are.”[1] M-ubuntu is a project that uses mobile devices to improve access to literacy tools in African schools. Geoff Stead stressed that M-ubuntu is about helping teachers to develop tools and practices to reform the educational system and engage learners. M-ubuntu relies on local champions to provide training on the ground and take the project further.

A lively Q&A session after the presentations saw an inquisitive audience still seeking answers to Niall Winters’ introductory questions. How sustainable and scalable are these ICT projects that had demonstrated an improvement in education in the developing world? To what degree are these collaborations dependent on NGOs, the private sector, and research institutions to move forward? How can we innovate in ways that are appropriate technologically and educationally?

The presenters acknowledged that they are still learners themselves in the young field of mobile education, and that the audience’s ‘constructive challenges’ were valuable as they move forward, together with overseas partners, in ‘the spirit of collaborative inquiry.’

By Anne Radl ~ 6 April 2011

Links

Where the action is: the foundations of embodied interaction, by Paul Dourish, MIT Press, 2004.

Researching mobile learning: frameworks, tools and research designs, Giasemi Vavoula, Norbert Pachler, Agnes Kukulska-Hulme ed., Peter Lang, 2009.

TRIBAL’s M-learning programme

[1] Leymah Gbowee